I love You, And I Am Not You.

Whenever I smell Old Spice or cigarette smoke, for a second, I look for Dad. Nothing brings him back to me more, and nothing reminds me more of how much I miss him.

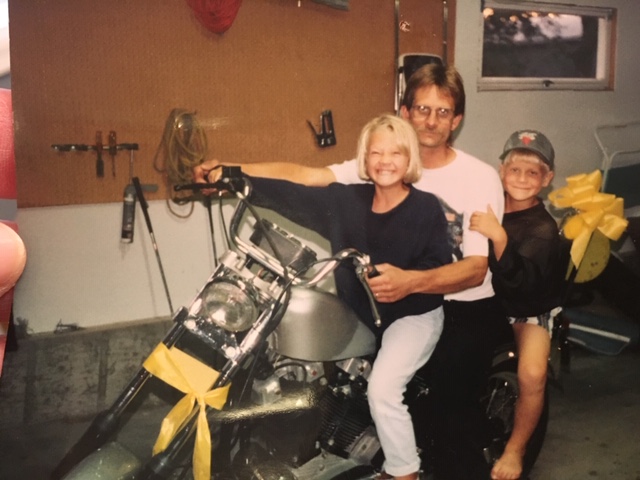

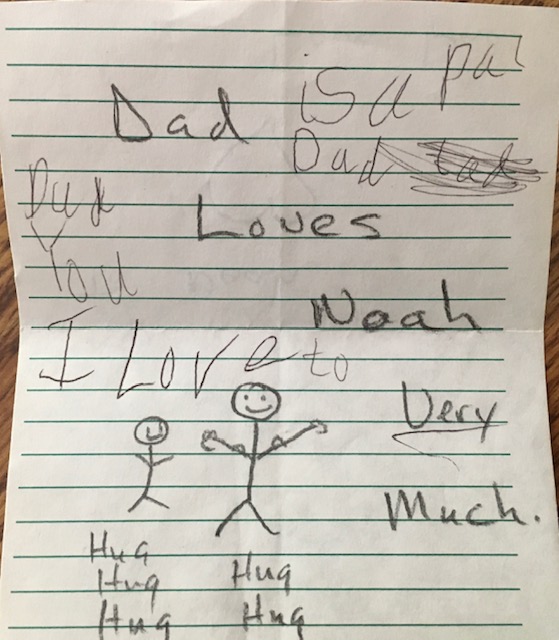

Once I was my dad’s little guy. He would kiss me good night on the forehead and tuck me in snug. Nothing could be sticking out, or the monster under my bed would grab whatever was hanging out, and I would be done for.

We had an imaginary friend, Fred. When we were driving, and one of us would point at imaginary Fred on a snowmobile or 4-wheeler keeping up with us on the highway. We would say something about how fast he was going and then – BAM! – we’d pretend Fred smashed into a light pole, and we’d laugh at how crazy he was.

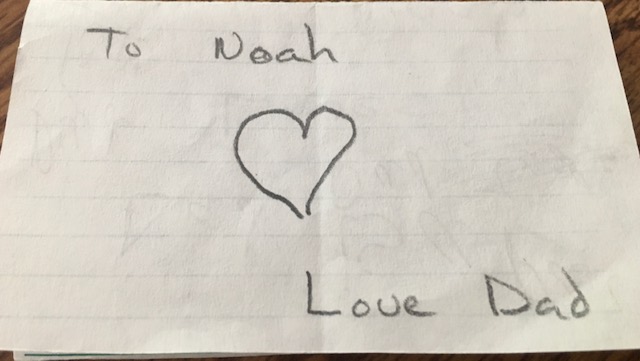

My father’s love was never a question. There wasn’t a second when I wondered if he cared about me. Even when he was mad at me or I crashed something of his, he would always make sure I wasn’t hurt before he asked about what I’d done. When he lost it, he wasn’t afraid to apologize and to explain why he was angry.

I wanted to be just like my dad.

He was a handyman who could fix anything, and as time went on, his shop became his escape. I didn’t go out there because I knew I wasn’t welcome. This was his time, and he wasn’t looking to share it with anybody else.

I snuck into his shop when I knew he wasn’t home, and I discovered why he didn’t want company: empty bottles of Smirnoff Vodka and ashtrays full of Swisher Sweets. It made sense that he didn’t want me to see him that way. I’d never seen him drink, but I guess at some point, he thought he needed something to soften the edge of his life.

I wanted to be just like my dad. I didn’t start drinking then, but I was watching. I did help myself to some of his Swisher Sweets. I thought he looked cool, so smoking must be cool. My first smoke were cigars that were so old they crumbled as I unwrapped the cellophane, I was 11.

When I was 17, my sister, Morgan, was in California going to school. My brother, Jesse, was in the Twin Cities at the University of Minnesota. My mom had gone back to school at the University of Minnesota, Crookston, to turn her two-year early childhood development degree into a bachelor’s degree for teaching. So that left dad and me at home together.

He was in pain; it wasn’t hard to see. It was etched in his eyes and his body. But I was a teenager and didn’t know shit about pain or how to help somebody with it. I spent the last two years of high school, watching Dad drink his pain away.

My parents’ marriage was on the rocks. It seemed they were staying together for the kids, and it was taking its toll on all of us. They were both exhausted from working relentless hours at the restaurant that was consuming their lives. My dad was in deep physical pain from working long hours under extreme stress. He was in emotional pain, living a life that had fallen short of his dreams. I want so much to go back and help him work through some of those problems, but it’s too late. He’s dead, and I’m here.

No matter how much you love your kids, living only for them is no way to live. When your kids witness you living a defeated life, a part of them is defeated, too.

That is what I saw in his eyes and his body: defeat. He would go to work early in the morning, come home, take a nap, watch TV, sneak out to his shop for multiple nightcaps, then get up and do it again.

He loved us, his kids, so much, but he somehow thought he had to sacrifice his own life to improve ours. Everything he did was for us.

I would have loved my dad whether he paid for my college or not, or whether he bought me a vehicle or not. I’m sure I would have been frustrated, but I would have gotten over it. He had already taught me that money isn’t everything, but then we both forgot to take his advice.

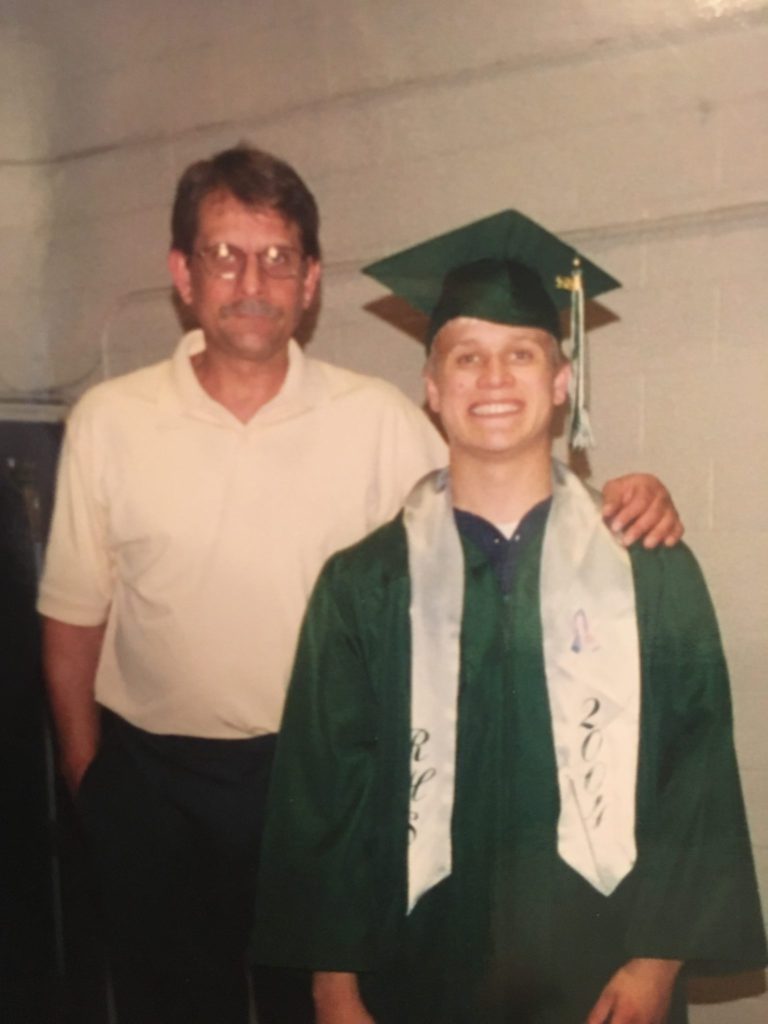

When I left for college, I didn’t know my dad would only live for three more years, but I should have.

I knew what he was doing, and I knew he couldn’t sustain the pace he was going. Then, I didn’t think he would crash as fast as he did, but I know now how fast addiction can take a life. I thought whatever was going on with him was none of my business, and I just needed to take his advice and get out of town. So I did.

When my dad died, I took his pain and buried it as deep as I could.

It burst to the surface every time I got into an altercation or when I failed at a relationship or a job or an opportunity. I coped with his death and any failure or stress with what I’d learned from him.

When I struggled with insecurity and feelings of inadequacy in high school, I self-medicated with alcohol. As personal losses and professional failures piled up, so did my feelings. I began to hate myself. Alcohol no longer cut it, so I moved on to more powerful medication.

As pain and failure collected in me, my drug use got out of control. I was rarely eating, never sleeping, and even bleeding out of my rectum. When my meth and crack addictions reached their peak, my insides literally began to rot. I’m ashamed, but that’s the monster of addiction.

My dad was easy going and passive with short bouts of rage from pent up emotions, just like me. When I was a kid, he once inexplicably shouted at me, punched a hole in my door, and ran off. I was completely baffled at the time, but since then, I have been in his shoes, more times than I can remember. Just like him, I can lose my temper over nothing when my feelings can’t be held back anymore. When I got raided, the cops asked why I had so many holes in the walls. I said, “Video games piss me off.”

When my dad died, I was furious. I felt he’d abandoned me, that he didn’t give a shit about who he’d left behind, and didn’t care to meet his granddaughter. He chose booze and cigarettes over us. And then, I chose selling and using drugs over my daughter.

I wanted to be just like my dad, and so far, that’s what I’ve done.

I had to forgive my dad, and I had to forgive myself for my part in the relationship. When he died, I was already a couple of years into heavy use with hard substances. As I wrote in Diving Deep into the Why: Part Five, my life was falling apart. I was isolating myself, especially from my family. I kept pulling money out of my hometown bank account, overdrawing it week after week. My parents got alerted, they’d put more money in, and then I’d do it again.

My parents called, but I wasn’t answering my phone. I still have that last voicemail that replays in my head from my dad, days before he died, telling me how much he loves me, is concerned and to call him back. It had been months since I had spoken to either of my parents. Eventually, I got another call. It wasn’t my dad; it was my brother. He didn’t want to talk about money. Dad was being airlifted to Grand Forks Hospital.

When we got there, he was in an induced coma. One at a time, we were each allowed to sit with him and say goodbye. I told him I was sorry, but I wondered if there is any point in saying anything.

No more than an hour after my sister arrived on a red-eye flight from California, he passed from pneumonia. He was holding on, waiting for her. He knew we were there. He heard me.

I miss my dad. I love him. And I won’t let addiction kill us both. I’m getting the second chance that he never got, and it’s up to me to make the most of it. I want to learn from his example, not follow it. I know that I need the strength and courage to ask for help. I know I must never stop working my recovery: to lean on my sponsor, my family, and my higher power. In his honor and mine, I’m ready to do that.

Two thumbs up was our thing. It’s how we would gauge where we were together and show our love. If I was mad at him, I would shake my head, scowl, and give him two thumbs down. But most times, we would see each other, say nothing and simply flash two thumbs up.

The signal is something we never grew out of, and it lasted until the very end. My dad always loved me, but he got hopelessly lost at some point in his life and never found his way back. Now I’ll work to get it back for both of us.

I love you and forgive you, Dad. And any time I smell Old Spice or cigarette smoke, I’ll be giving you two thumbs up.

[…] I didn’t call. My mom or dad would have driven down in a heartbeat, but I didn’t call (or answer the phone). When you are an addict, it doesn’t seem that […]