Recently, there’s been a movement to abolish prison labor. With prisoners getting paid pennies an hour and corporations profiting from prisoners’ labor, it may seem from the outside that abolishment is the obvious and ethical approach.

Whenever I read an article about abolishing prison labor I think, “There’s no way this person has ever been to prison or supported someone who’s been to prison.” The articles on this topic are usually not talking about the typical prison jobs, however. Most are referring to Federal Prison Industries, Inc., such as UNICOR or some other sort of work program.

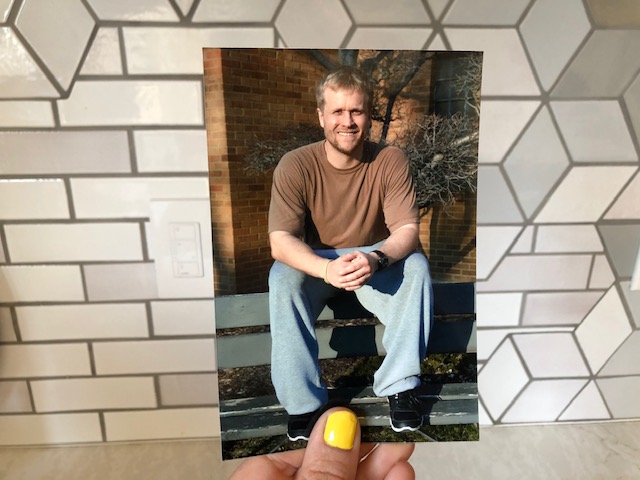

But prison labor is complicated. I’m an ex-con who served seven years in the federal prison system and worked a wide array of jobs. I cleaned units, worked the kitchen, cleaned the compound, and worked in the facility’s paint shop.

I never made enough working a prison job. To be comfortable, an inmate needs anywhere from $100-$200 in extra spending money a month. The Bureau of Prisons does provide all the necessities but the quality is very poor, and some people are forced to live off of them, but those people are not comfortable.

They don’t eat when they want, drink coffee when they want, and most nights go to bed hungry. They brush their teeth with the world’s smallest toothbrush and worst tasting toothpaste, the soap dries their skin out faster than the Arizona sun, and their underwear is largely made of polyester. Phone calls, due to the cost, aren’t an option, and stamps for letters might be out of their price range.

You can argue this is part of the deal, they’re getting what they deserve and reaping what they sow, but I’ve been there with them and feel a different way. I felt bad every time I saw an inmate wear nothing but government-issued khaki pants, a white tee, and black military boots because I knew they couldn’t afford to buy some more comfortable attire, like sweats, basketball shorts, and a new pair of sneakers.

My first taste of prison labor was in Milan, Michigan working in the kitchen for roughly 110 hours a month making $18.50. Yes, you heard that right, $18.50 a month.

In my seven years in prison, the most I ever made in a month was $90 ($60 + $30 bonus). The bonuses were dispersed depending on how much money was left on the budget and were given to the highest grades first and then down the line of seniority from there. For my $90, I worked 161 hours, so, with a bonus, I made just over 50 cents an hour. I felt so rich that month but it only happened a couple of times before bonuses’ were cut.

$90 for 161 hours of work sounds like a modern form of slavery, but believe it or not, I do not think prison labor should be abolished.

Work in prison isn’t just about the money. Don’t get me wrong, I always needed more money and I always tried to get a better-paying job wherever I was. But what I realized is that doing time was easier if I stayed busy.

In prison, everybody has to have a job but if you don’t want to work, you don’t have to. You can get assigned to a job and then pay someone your monthly wage to fulfill your duties.

There are other jobs that pay next to nothing but you do next to nothing. I tried that.

My job at the night compound paid $5 a month. Every evening after dinner, I would go over to the compound office, give them my name, and that was it.

I did that for a couple of months: I worked out a lot, played cards, watched sports. After a while, I started going crazy. I felt like an unemployed person, with no money, no purpose, and I had way too much time ahead of me for that.

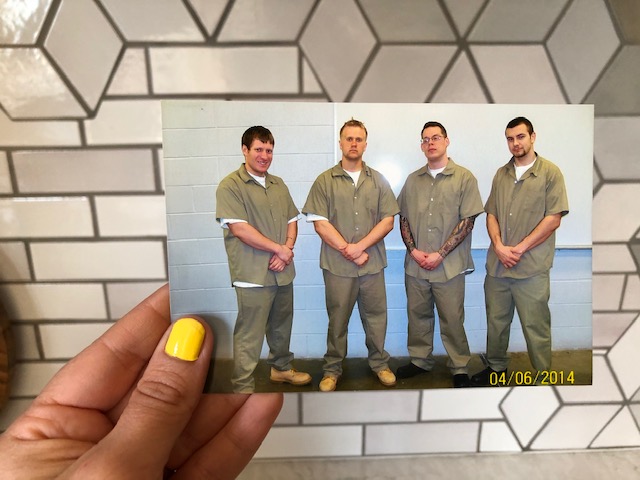

UNICOR is a work program, that is not available at every federal institution, and fulfills government contracts for both the military and for other prisons making clothing, lockers and bunk beds, and really anything else you find in a prison or barracks.

UNICOR makes a massive profit with these contracts and in part by paying its employees (inmates) on average between $0.23 and $1.15 an hour accompanied by a bonus which allows slightly higher wages. It sounds abusive, I know, but prison labor is more complicated than money.

There was a UNICOR program at the Federal Prison in Milan, Michigan, where I did 18 months of my sentence. I never worked there but I hung out with plenty of inmates that did. When I recently asked them about their experience and if they think the programs should be shut down, they all said the same thing, “Are you kidding me? Hell no!”

According to the men I talked to, these programs were the difference between relying on the outside world for money and taking care of themselves. UNICOR workers had a feeling of self-worth and self-respect. Some used the money to buy Christmas and birthday presents for their children and spouses. Some sent money home to help out with bills, while others just lived a comfortable life in prison without having to ask for help.

Most incarcerated people are always thinking about two things: food and money. Inmates live for their next meal which is usually not worth eating, which circles them back to, “How can I make more money to buy my own food from the commissary or the canteen.”

I know inmates who did not want to leave the facility they were in because the one they were being transferred to didn’t have a UNICOR program and they were scared shitless of going back to having no money. They were willing to stay at a higher-level security facility where there was violence in exchange for higher wages.

It’s not just the money but the skills, structure, and purpose these jobs offer that make them valuable. The majority of inmates haven’t had much structure in their lives, at least not professionally. Often UNICOR is their first real taste of working a 9-5. The work teaches inmates responsibility, as they’re expected to be on time, held accountable for their work duties, and to standards that any other workforce expects.

Some inmates owe restitution for their crimes and if they work at UNICOR, a portion of their check every month goes towards that payment. I’ve seen inmates pay back tens of thousands of dollars in restitution and go home debt-free.

Last but maybe most importantly, UNICOR shows them their potential and teaches them life skills. They start to experience stability because they begin to earn a paycheck that supports them. They also build confidence and independence, as they begin to realize they can work a normal job, not go back to the street life, and still provide for themselves and their families upon release.

From the outside looking in it’s easy to say inmates aren’t paid enough and shouldn’t work for low wages. I agree that non-UNICOR jobs that pay 17-55 cents an hour take advantage of incarcerated people. I think it’s worth working to increase those wages. But to eliminate the only jobs paying over or close to, a dollar an hour, while teaching the inmates life skills, would be a disservice only to the inmate.

People in the free world might have a different perspective, but $1 per hour for an inmate could mean, a paid debt, family support, and dignity. It may not sound like much but I know inmates who make $200-300/month on a regular basis and in prison, this is a life-changing income.

So, when I hear someone arguing against programs like UNICOR, I urge them to do more research, talk to the inmates who have worked the jobs, the families who have been relieved of a burden, and the victims who have been paid back.

Inmates don’t get paid enough and there certainly are improvements that can be made to prison labor. I will fight for paying them higher wages until the day I die, but cutting the highest paying programs they have is not the answer. In fact, I wish there was a UNICOR or something like it at every federal and state facility, so inmates have options.

Every day inmates lose something, in fact, it’s all they know. Whether it’s a possession taken from a guard, a privilege lost from another inmate’s poor behavior, a monthly bonus at work, a dumbbell from the weight room, or simply the time they are serving. Taking more from them is not the solution.

Let’s stop focusing on what we can abolish and instead find out what we can help them obtain. A higher wage at their prison job, more visitation hours during the week, more furloughed passes at lower-level facilities, and an early release from prison.

Related Articles about Prison

Prison Jobs, Hustles, Cash, and Phones

7 Ways to Support Someone in Prison

4 Ways to Support Someone Post Prison