Table of Contents

My Nephew & Me: Writing for Change

The day before my wedding in October 1999, I was a childless, 35-year-old woman with two parents and one sister. The next day, I gained not only a husband, two step-kids, parents-in-law, and four siblings-in-law, but 13 nieces and nephews and two great-nieces and nephews (that number is now up to 17).

It was overwhelming. That first year, just keeping the brothers and sisters straight was challenging, but remembering which kids went with who and what all the intersecting relationships were? My brain couldn’t take it in. The first Christmas I spent in Minnesota with them all, I regularly hid in the bedroom just so I could put my head down.

Even in the crazy conglomeration of cousins, though, Morgan and Noah stood out.

Morgan, 15 when I joined the family, was sunny and smiling, silly and sweet. She laughed often and easily and told wild stories of waitressing that got everyone laughing and amazed by what she could create just by being herself.

And Noah. Noah always felt like a storm cloud ready to burst. Even at 14, his reckless and dangerous choices made my stomach hurt. I watched him warily and steered clear. I was afraid of what this balls-to-the-wall teenager might do.

In 2012, when news came through the (elaborate and long) family grapevine that Noah was going to prison, I wasn’t shocked. I didn’t know him at all and I sure didn’t know the whole story. I just knew that I felt the same way around Noah as I did as a kid with an irresponsible babysitter: this person is unreliable, dangerous, and out for nobody but himself.

The Wedding Before Prison

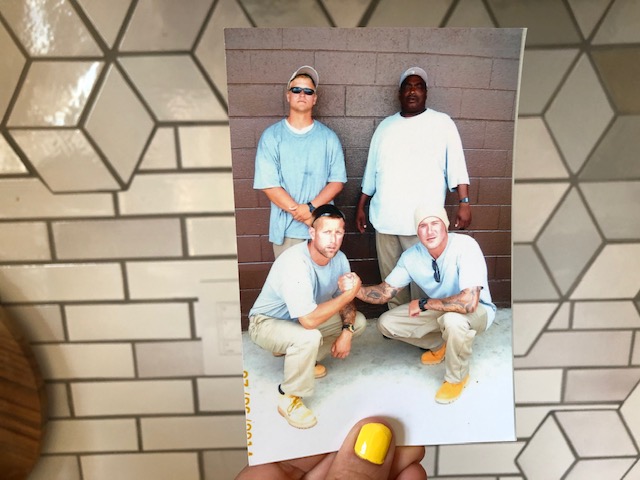

When Morgan got married in 2013, Noah was there. Somehow, he’d managed to delay his sentence until the day after her wedding. I still had a nervous stomach around him so all weekend, I eyed him from a distance. He held himself steely, stony, and armored. He took a no-big-deal tone about starting his sentence.

But I didn’t buy it.

I didn’t know this kid at all. But I believed that under his hyper-masculine toughness, he had to be scared shitless. He had to be.

I didn’t know anything about the correction system or what he was facing, but I knew he had a 2-year-old daughter. I knew that he’d burned bridges in the family. I imagined that most people, me included, felt like he pretty much got what was coming to him.

Seeing him, handsome in his groomsman clothes, grinning for pictures and dancing with his daughter, I wondered what it would feel like to be Noah. What would I want if I was looking down the barrel of a decade in prison?

I had no idea. Maybe I’d want to know that I hadn’t been forgotten. Maybe I would want to know that I mattered to someone.

That evening, I decided to write to Noah during his incarceration. It seemed like a small, easy thing to do. On the plane back from Minnesota, I told my husband, Frank about the idea. “You know,” I said, “some people go to prison and totally turn their lives around. Maybe he will come out and help people. Maybe he’ll write a book. Maybe he’ll make a difference in the world.”

Frank looked at me for a minute and said, “Maybe.”

As soon as I was home, I logged into the antiquated, awkward Bureau of Prisons email system and sent Noah a message.

What do I say?

Every two weeks.

I promised myself I’d write every two weeks. And every two weeks, I got a sick feeling of dread. What do I say to a guy I don’t know who’s been sentenced to 10 years in the federal prison system?

“How’s it going?”

Good God, that’s a stupid question. I know how it’s going. It’s going terrible, that’s how it’s going.

“What are you up to?”

Stupider still. I didn’t want to know and he probably didn’t want to tell me.

Do I tell him about what we’re doing? Tell him about our lives out in the world, working and traveling, connecting with family, doing all the things he can’t do? Do I tell him about our kids, his cousins, who are in school, building careers, getting engaged, and living life? That seemed unkind, cruel even.

I casted about. I wrote painfully short, tedious emails. He wrote back the same way. He told me about fights over what sports to watch on TV. About how bored he was. He asked for a subscription to Golf magazine.

Every two weeks for two years we exchanged stiff emails. Every two weeks and it was painful every time.

Scary Prison vs. Prison Camp

The first place Noah landed, the Federal Correctional Institution in Milan, Michigan is a low-security facility with about 1600 inmates. Based on his description, I thought of Milan as a “scary prison.” I imagined Noah trapped on a cold, gray concrete block with nothing to do: no work, no recovery programs, no education, no creative possibilities. Just lots of scary, angry, violent inmates with a ton of time on their hands.

But in 2015, Noah was transferred to Yankton Federal Prison Camp in South Dakota for good behavior. A prison camp, Noah explained, was lower security than Milan had been. There, the inmates were part of how the facility run. They were in charge of the food, the laundry, maintenance, and grounds.

At Yankton, Noah had work to do, sometimes even outside the compound. His spirits improved. He had more news to tell. He sounded more optimistic. He took classes, built skills. And most importantly in 2018, he started a recovery program.

And as part of his recovery, Noah started writing.

Writing it Out

Impact letters are often part of recovery programs: an addict’s loved ones write letters about the full impact of his choices on their lives and hearts. Those letters are tough to write and tougher to read. Impact letters are full of pain, anger, hurt…and love. There can be no deep grief without deep love.

When Morgan wrote her impact letter to Noah, he wrote her back. The two of them corresponded about the most difficult and painful part of their relationship.

Ever the creator of amazing things, Morgan runs a popular blog for her family’s renovation contracting business, construction2style. In 2019, Morgan did something extraordinary with her platform. Thinking that others might benefit from knowing about Noah’s journey, the two of them decided to post their correspondence on her blog.

And people responded. Someone had a child/friend/brother in prison and they were relieved to have someone talk about it. Another’s loved one was about to go into prison and they were terrified. Her parent had been in a facility for decades and was about to get out and she didn’t know what to do. And lots of people and families dealing with addiction needed encouragement and hope.

So in addition to his letters with Morgan, Noah wrote about life in prison, what got him there in the first place and about his recovery. He wrote to his younger self about what he wished he’d known. He wrote about fights and funny stuff and fear.

I read every post as soon as it went up. I read about his self-destructive choices, all the dangers of dealing drugs, his unsettled childhood. I read about the thrill of using, all the things he wanted to numb out and forget about, the pain of hurting the people he loved the most. His writing had me laughing at his show-off antics, gasping at the trouble he got in, shaking my head at how hard he was on himself. Over and over, his enthusiasm, his insecurities, his struggles broke my heart.

As soon as I read a post, I’d email Noah. I was full of questions and asked him to tell me more details of his experiences before and during prison. I wanted to know about what he missed about his drugging life and what he regretted. I kept asking him to tell me not just what happened, but how he felt about it.

Before Noah, I’d given next to no thought to the prison system or the inmates that found themselves there. Psychologists and philosophers call it “othering:” the practice of excluding and displacing certain people from their social group to the margins of society, where mainstream social norms do not apply to them. Othering is what makes it possible for humans to treat each other as inhuman. And that’s what I’d been doing with people in prison.

At about the time Noah started writing, I found Ear Hustle, a podcast created by inmates at San Quentin State Prison in California. Each episode is about an aspect of prison life ~ picking a cellmate (a cellie!), the food, parenting from prison or relationships with women while inside. It opened my eyes and heart to the brutal inhumanity of prison life and the deep humanity of the inmates. So I’d listen to Ear Hustle and write Noah to ask if his experience was anything like theirs.

What had been a painful correspondence became a wonder of discovery and understanding. The more I learned about the correctional system, his friends, his recovery, the more questions I had. Instead of once every two weeks, we were writing every two days. Based on my incessant questions, he would write posts that would spur more conversations and more posts.

And this man who I’d never liked and had been afraid of became someone I loved to talk to, loved to banter with, loved getting to know. Noah, of all people, became my friend.

Working Together

During a visit in late 2019, Noah and Morgan got an idea. They wanted to start a website for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated folks and the people who loved them. They wanted to create a place for inmates and former inmates to tell their stories, for people in recovery to talk about their process, for everyone to see the humanity of people behind bars, to help people who end up in that situation. They wanted to call it resilience2reform and I thought the idea was genius.

I’d been an English major in college and my first career was as an editor in educational publishing. Although I haven’t worked in publishing for decades, when Morgan told me about resilience2 reform, I told her I wanted to be part of it.

Noah wrote posts and I read them before they were published: asking for more detail, digging for definitions when he tossed around inmate-speak, editing for clarity. He was a joy to work with: incredibly courageous, eager to learn, and committed to writing the best, most helpful pieces he could. I loved watching his writing evolve and got excited every time a new draft hit the blog.

COVID Release

In late April 2020, I got the last email from Noah in prison. It was short, obviously written in a hurry: they are letting me go early, I’m going into quarantine and I won’t be able to write anymore. I’ll be out in May.

On May 7, 2020, Noah was released from Yankton Prison Camp: a gift of the COVID-19 outbreak in the prison system. Four months and two days before his sentence was up, he was let go to home confinement with his mom, my sister-in-law, Mary.

Mary, Morgan, Noah’s daughter, Melrose, and his brother, Jesse drove to Yankton to pick Noah up. Morgan, in true blogger style, took a video of their reunion on the sidewalk outside the prison camp. I watched that video over and over and cried every time.

I was happy for Noah, of course. Happy for his daughter and mother and sister and brother. But I was also happy for me. Happy for our friendship, happy that I would be able to connect with him more easily now he was out in the world, happy to see what he would do with his second chance.

I thought about the seven years we’d been corresponding. I thought about how many assumptions I’d made about him and how easy it would have been to write him off as a fuck up and a loser. I wondered how often I’d done that to other people in my life. I was just glad that we kept writing every two weeks.

On the way home from Yankton, Noah called me from the car. I was half laughing, half crying, saying “holy shit, Noah” more than an Auntie probably should. He had tons of people to call, so I let him go. But before we hung up, I said, “I love you, Noah.”

“I love you, too.”

[…] writers on r2r are people who have been through enormous trauma and suffering (some self-imposed) and are making […]